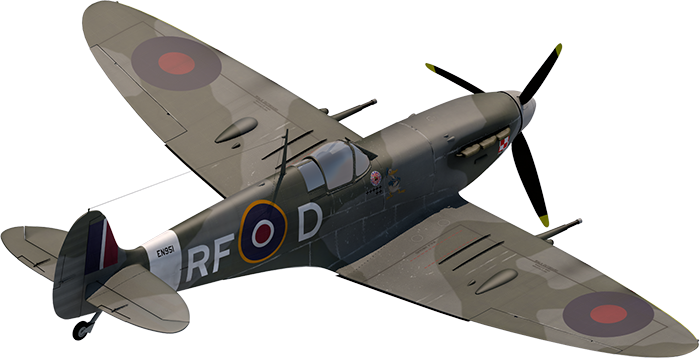

History of the Spitfire

A masterpiece of aerodynamic engineering

Many consider the Spitfire to be a masterpiece of aerodynamic engineering, and was among the finest fighter aircraft of the Second World War.

Spitfires have hit the ground, touched the sea, bashed through trees, cut telegraph lines and had wings fall off, and have yet made safe landings, with or without wheels.’ So wrote Australian Spitfire pilot John Vader.

Origins of the Spitfire

In 1931 the Air Ministry released specification F7/30, calling for a modern fighter capable of a flying speed of 250 mph (400 km/h). R. J. Mitchell designed the Supermarine Type 224 to fill this role.

The 224 was an open-cockpit monoplane with bulky gull-wings and a large, fixed, spatted undercarriage powered by the 600 horsepower (450 kW), evaporatively cooled Rolls-Royce Goshawk engine. It made its first flight in February 1934. Of the seven designs tendered to F7/30, the Gloster Gladiator biplane was accepted for service.

The Type 224 was a big disappointment to Mitchell and his design team, who immediately embarked on a series of “cleaned-up” designs, using their experience with the Schneider Trophy seaplanes as a starting point. This led to the Type 300, with retractable undercarriage and a wingspan reduced by 6 ft (1.8 m).

This design was submitted to the Air Ministry in July 1934, but was not accepted.

It then went through a series of changes, including the incorporation of a faired, enclosed cockpit, oxygen-breathing apparatus, smaller and thinner wings, and the newly developed, more powerful Rolls-Royce PV-XII V-12 engine, later named the “Merlin”.

In November 1934, Mitchell, with the backing of Supermarine’s owner Vickers-Armstrong, started detailed design work on this refined version of the Type 300.

On 1 December 1934, the Air Ministry issued contract AM 361140/34, providing £10,000 for the construction of Mitchell’s improved Type 300, design. On 3 January 1935, they formalised the contract with a new specification, F10/35, written around the aircraft.

K5054 was fitted with a new propeller, and Summers flew the aircraft on 10 March 1936; during this flight the undercarriage was retracted for the first time.

After the fourth flight, a new engine was fitted, and Summers left the test-flying to his assistants, Jeffrey Quill and George Pickering.

They soon discovered that the Spitfire was a very good aircraft, but not perfect. The rudder was oversensitive, and the top speed was just 330 mph (528 km/h), little faster than Sydney Camm's new Merlin-powered Hurricane.

A new and better-shaped wooden propeller allowed the Spitfire to reach 348 mph (557 km/h) in level flight in mid-May, when Summers flew K5054 to RAF Martlesham Heath and handed the aircraft over to Squadron Leader Anderson of the Aeroplane & Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE).

Here, Flight Lieutenant Humphrey Edwardes-Jones took over the prototype for the RAF. He had been given orders to fly the aircraft and then to make his report to the Air Ministry on landing. Edwardes-Jones' report was positive; his only request was that the Spitfire be equipped with an undercarriage position indicator.

A week later, on 3 June 1936, the Air Ministry placed an order for 310 Spitfires, before the A&AEE had issued any formal report. Interim reports were later issued on a piecemeal basis.

Spitfire Mark I

After consultations with RAF technical experts, the armament for the new Spitfire fighter was settled on 8 Browning .303 machine guns. These were basically Colt .30s manufactured under licence but re-chambered to take the British rimmed cartridges.

They were placed four to a wing, a novel concept at the time, and designed to fire outside the circle of the propeller, doing away with the need for the interrupter gear of earlier aircraft.

Smith also simplified the construction and design to make the Spitfire more amenable to mass production, and he finally brought Mitchell’s idea to a practical conclusion when the first Mark I, K9789, officially entered service with No 19 Squadron at RAF Duxford on 4 August 1938. The first few planes had only four machine-guns, as there was a desperate shortage of Brownings at the time.

The Production Line

The British public first saw the Spitfire at the RAF Hendon air-display on Saturday 27 June 1936. Although full-scale production was supposed to begin immediately, there were numerous problems that could not be overcome for some time, and the first production Spitfire, K9787, did not roll off the Woolston, Southampton assembly line until mid-1938.

In February 1936, the director of Vickers-Armstrong, Sir Robert MacLean, guaranteed production of five aircraft a week, beginning 15 months after an order was placed. On 3 June 1936, the Air Ministry placed an order for 310 aircraft, at a cost of £1,395,000.

Full-scale production of the Spitfire began at Supermarine’s facility in Woolston, but it quickly became clear that the order could not be completed in the 15 months promised. Supermarine was a small company, already busy building Walrus and Stranraer flying boats, and Vickers was busy building Wellington bombers.

The initial solution was to subcontract the work. Although outside contractors were supposed to be involved in manufacturing many important Spitfire components, especially the wings, Vickers-Armstrong (the parent company) was reluctant to see the Spitfire being manufactured by outside concerns, and was slow to release the necessary blueprints and subcomponents.

As a result of the delays in getting the Spitfire into full production, the Air Ministry put forward a plan that its production be stopped after the initial order for 310, after which Supermarine would build Bristol Beaufighters.

The managements of Supermarine and Vickers were able to convince the Air Ministry that production problems could be overcome, and a further order was placed for 200 additional Spitfires on 24 March 1938. The two orders covered the K, L and N prefix serial numbers.

In mid-1938, the first production Spitfire rolled off the assembly line and was flown by Jeffrey Quill on 15 May 1938, almost 24 months after the initial order. The final cost of the first 310 aircraft, after delays and increased programme costs, came to £1,870,242 or £1,533 more per aircraft than originally estimated.

A production aircraft cost about £9,500. The most expensive components were the hand-fabricated and finished fuselage at approximately £2,500, then the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine at £2,000, followed by the wings at £1,800 a pair, guns and undercarriage, both at £800 each, and the propeller at £350.

Initial Operational Performance

The early Mark Is had a service ceiling of 31,900ft, and at 30,000ft could reach a speed of 315mph.

Its maximum speed was 362mph at 18,500ft.

Its maximum cruising speed, though, was 210mph at 20,000ft, and at economical speed its range was 575 miles.

Its combat range was 395 miles, allowing for take-off and 15 minutes of fighting. By the time the Spitfire had brought down its first German plane, a Heinkel He 111 bomber over the Firth of Forth on 16 October 1939, several improvements had been made to the Mark I.

To its elliptical wings and all-metal ‘monocoque’ body, where the skin is part of the plane’s structure rather than just a covering, had been added the bulged, or blister-shaped, cockpit, thereby completing the Spitfire’s classic profile.

Windscreen plastic had been replaced by armoured glass, armour plate was fitted at the rear of the engine bulkhead, a power-operated pump was installed to operate the undercarriage, and the tail-skid had been replaced by a wheel.

The Merlin Mark II engines were giving way to the Mark III with its improved airscrew shaft, and the two-blade wooden propeller had been replaced by the De Havilland three-blade metal, two-pitch propeller, significantly enhancing performance, particularly in the climb.

Remodelling and Rearming

The Mark II had better protection for the pilot as well, with increased armour behind the pilot’s seat to protect his head. Another early development which led to increased Spitfire variety was the production of different wing types to accommodate a range of different armament set-ups. The A wing was the original one designed to hold four .303 machine guns. The B wing was designed to accommodate the newly accepted Hispano-Suiza 20mm cannon, so each wing had one cannon and two .303 machine guns.

Most of the Spitfires with which the RAF fought the Battle of Britain were Mark Is, but work had begun on a Mark II as soon as the first model had gone into production, and some were already in service as early as the summer of 1940. There was little difference between the two marks, the main one being that the Mark II Spitfires were fitted with the Merlin XII engine, rated at 1150hp. The Spitfire Mark II had slower maximum and cruising speeds, but a faster climb rate, being able to reach 20,000ft in 7 minutes, and had an improved ceiling of 32,800ft.

The C, or ‘Universal’, wing could accommodate either the A or B combinations, or an altogether new combination of two 20mm cannons. There was no D wing, but an E wing was created, which carried a 20mm cannon and a .50in machine gun. Fifty Mark IBs were manufactured, but there were problems with ammunition feed to the cannons. By the time the Mark II was ready to enter service, this problem had been resolved. Of the 920 Mark IIs made, some 170 (23%) had the B-wing combination (the cannon variant).

In the continual programme of updating and improving the Spitfire, the next most significant development was the Mark V (which is the variant built as a life size model in this hangar), and with a production run of nearly 6,500, this was the most common type ever produced. They were manufactured mostly in the B and C versions. Some with the Universal wing were given four cannons and could carry one 500lb bomb or two 250lb bombs. They were also fitted with drop tanks of 115 or 175 gallons, significantly increasing endurance.

Faster and Higher

The Mark V Spitfires were powered by the Merlin 45 and 46 engines, producing 1470hp at 16,000ft.

These new, more powerful Spitfires were the Air Ministry’s response to the introduction of the Messerschmitt Me 109 F and the Focke-Wulf FW 190 in the spring of 1941, both of which clearly outclassed the Spitfire Mark II.

The Mark VAs could reach a speed of 376mph at 19,500ft, at which height the Mark VB’s speed was 369mph, whilst the Mark VCs reached 374mph at 13,000ft. The climb performance of the Mark Vs was improved, being able to reach 10,000ft in 3 minutes 6 seconds, and 30,000ft in 12 minutes 12 seconds. The Spitfire’s ceiling was also raised by some 2,000ft.

As aircraft design and performance improved on both sides, as did the number of roles they were asked to perform increased. The Spitfire proved its versatility as a new range of designations was introduced. Those Spitfires designed for high-altitude work were given the preface HF, those for low-altitude LF, and those for normal duties F.

The HFs and LFs were given variations of the Merlin engine specifically designed for their tasks.

The HFs were distinguishable by their extra long wing-tips, whereas the LFs had clipped wings.

Developments and adaptations continued to the end of the war, with the Mark IX taking over from the Mk V as the most commonly manufactured plane of the later series, with some 5,500 produced, of which more than 1,000 went to Russia.

Increasing numbers of Spitfires were also being sent to the Middle Eastern and Far Eastern theatres of operations.

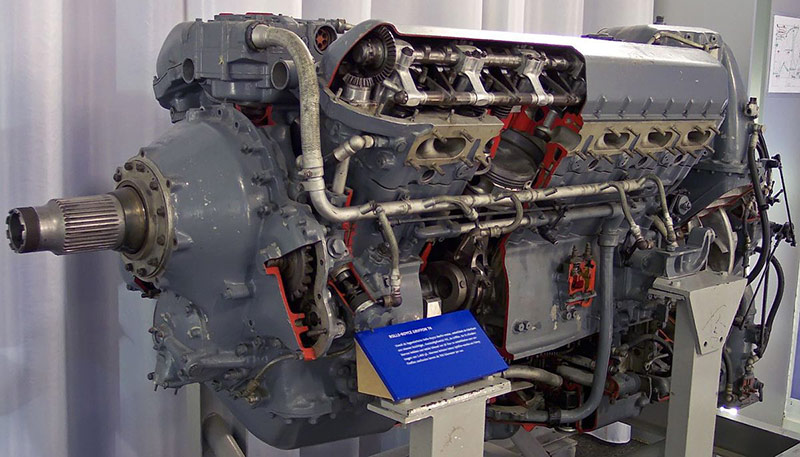

The Griffon Engine

Experiments had been ongoing with the new Rolls-Royce Griffon engines. The first of the production Spitfires with these engines was the Mark XII with the Griffon III or IV, followed by the Mark XIV with the 2050hp Griffon 65, driving a five-blade Rotol propeller. The Mark XIV had a maximum speed of 443mph at 30,000ft, and could reach a height of 12,000ft in just 2 minutes 51 seconds. It was a Mark XIV which was the first Allied plane to bring down a Messerschmitt Me 262, the world’s first operational jet fighter.

The appearance of the Me 262, however, showed the way to the future. After the war, designers everywhere turned to the production of jet-engined fighters. The Spitfire’s postwar service life was brief although included action in Malaya and Korea.

Speed

and

Altitude Records

Beginning in late 1943, high-speed diving trials were undertaken at Farnborough to investigate the handling characteristics of aircraft travelling at speeds near the sound barrier (i.e., the onset of compressibility effects). Because it had the highest limiting Mach number of any aircraft at that time, a Spitfire XI was chosen to take part in these trials. Due to the high altitudes necessary for these dives, a fully feathering Rotol propeller was fitted to prevent over-speeding. It was during these trials that EN409, flown by Squadron Leader J. R. Tobin, reached 606 mph (975 km/h) (Mach 0.891) in a 45° dive.

In April 1944, the same aircraft suffered engine failure in another dive while being flown by Squadron Leader Anthony F. Martindale, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR), when the propeller and reduction gear broke off. The dive put the aircraft to Mach 0.92, the fastest ever recorded in a piston-engined aircraft, but when the propeller came off the Spitfire, now tail-heavy, zoom-climbed back to altitude. Martindale blacked out under the 11 g loading, but when he resumed consciousness he found the aircraft at about 40,000 feet with its (originally straight) wings now slightly swept back. Martindale successfully glided the Spitfire 20 mi (32 km) back to the airfield and landed safely. Martindale was awarded the Air Force Cross for his exploits.

On 5 February 1952, a Spitfire 19 of 81 Squadron based at Kai Tak in Hong Kong reached probably the highest altitude ever achieved by a Spitfire. The pilot, Flight Lieutenant Edward Ted Cyril Powles, was on a routine flight to survey outside-air temperature and report on other meteorological conditions at various altitudes in preparation for a proposed new air service through the area. He climbed to 50,000 ft (15,000 m) indicated altitude, with a true altitude of 51,550 ft (15,710 m). The cabin pressure fell below a safe level and, in trying to reduce altitude, he entered an uncontrollable dive which shook the aircraft violently. He eventually regained control somewhere below 3,000 ft (910 m) and landed safely with no discernible damage to his aircraft. Evaluation of the recorded flight data suggested he achieved a speed of 690 mph (1,110 km/h), (Mach 0.96) in the dive, which would have been the highest speed ever reached by a propeller-driven aircraft if the instruments had been considered more reliable.

Fly the Spitfire Simulator. Enquire now!